The next tutorial in learning how to program in Python is focused on strings and string methods…

Let’s jump right back in! It’s time to talk about strings (and I’m not talking about the ~120 different shoe strings I currently possess…)! Strings are something that denote collections of text in programming.

Programmers handle text data on an almost daily basis. As a machine learning engineer, I deal with text data all. the. time. From text analysis, to natural language processing, to extracting data to perform sentiment analysis, collections of text, aka strings, are everywhere, and knowing how to deal with text data is vital.

Programmers can manipulate strings by using special functions called string methods. There are string methods for doing just about anything; for example, changing a string from upper case to lower case, lower to upper case, replacing parts of the strings with different text, and so much more!

In this tutorial, you will learn a ton about strings. Namely:

- What exactly a string is and when to use it

- How to use string methods to manipulate strings

1. What is a String?

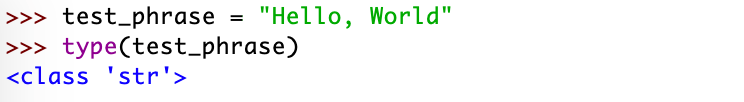

If you read First Steps… Python 101 you will have dealt with strings already! Particularly, when you created the string “Hello, World” and displayed the output using the print() function. Variables can store different data types which can do different things, and strings are one of the most important and fundamental data types in Python.

Variables can store different data types which can do different things, and strings are one of the most important and fundamental data types in Python.

A data type is a way of describing what kinds of data different values consist of. There are many different data types built into Python, and strings are used to represent text data. Some other data types you will learn about are numerical data types, which represent numbers, and boolean data types, which are used to represent a value of True or False.

Strings are such a vital and fundamental data type because they cannot be broken down into different types of smaller values; although, not all data types are considered fundamental. In Python, we can denote strings in a special way: str. To determine the data type you may be working with, you can use the function “type()”, similar to the “print()” function.

Open IDLE, and type the following into the interactive window:

So, what does “<class ‘str’>” mean? This simply means that the value “Hello, World” is an instance of the string – str – data type… or simply that “Hello, World” is a string! The word class, in this case, can be used as a synonym for data type although a class in object oriented programming is something that you will see in a later tutorial.

Strings have many important properties. The three most important properties include:

- Containing characters, which are individual symbols or letters

- Characters appear in a numbered position within the string, which is called a sequence

- Strings have a defined number of characters, called the length

You can also use the “type()” function to see the data type of values that have already been assigned to a variable. For example:

This simply means that the data type of the variable is… drum roll… a string!

2. Manipulating Strings

Let’s go through how to do some basic string manipulations.

As you saw in the previous tutorial, string literals are created by surrounding the text with quotation marks. Anything inside the quotation marks is a part of the string. Since you’re now officially a master of creating strings, you know you can only create a string using single or double quotation marks, as long as you use the same type at the beginning and the end of the string. Let’s review string literals using the previous example:

All of the strings you have seen so far are string literals. The name reminds us that the string is written out in your code literally. There are strings, however, that are not string literals. Any string that is not explicitly typed out in your code, whether that be from user input or text being read in from a file, is not a string literal, because it was not literally typed in quotation marks in your code.

Let us break down further some important parts in the strings. The quotation marks that surround the string are called delimiters. Delimiters tell Python where the string begins and ends. When you use one type of quotes as the delimiter to begin the string, you can then use the other type of quotes inside the string. Examples of this include:

Python determines that the first quotation mark is used as the delimiter, so it considers everything after that a part of the string until it finds a matching delimiter. Thus, you can use the first as a delimiter, while using the second quotation mark as a part of the text.

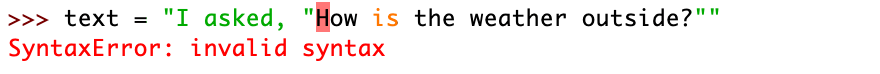

You will encounter an error if you try to use double quotations inside of a string delimited by double quotations:

The SyntaxError occurs because Python believes the string ended after it found the second double quotation mark, and it doesn’t know how to read the rest of the text.

Note: it’s a good idea to use only double or single quotation marks to delimit every string in your code.

Any valid Unicode character can be included in a string, including “#”, “$”, even “ęûøÿñ” is a valid string in Python.

2.1 Multiline Strings

According to the PEP 8 recommended styling guide for Python code, each line of code should not have more than seventy-nine characters including spaces. While we will continue to follow PEP 8 styling guide, there will be instances where you may need more than seventy-nine characters per line. In this instance, you can break up the code amongst multiple lines called multiline strings. Suppose you have the phrase:

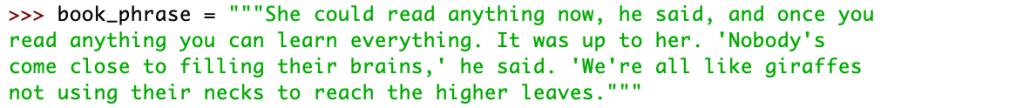

“She could read anything now, he said, and once you can read anything you can learn everything. It was up to her. “Nobody's come close to filling their brains,” he said. “We're all like giraffes not using their necks to reach the higher leaves.”

― Delia Owens, Where the Crawdads SingSide note: Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens is my all time favorite book and if you enjoy reading I suggest checking it out!

What to do when you have a phrase that is clearly longer than seventy-nine characters?

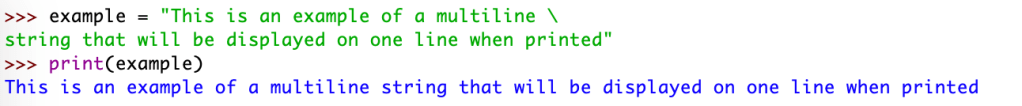

One way to adhere to PEP 8 styling and accomplish this task is to use a method of escaping using the backslash (\) at the end of every line except the last. For example:

Note: you do not need to end each line with a matching quote because you included the backslash at the end. When Python sees the backslash, it knows that your string continues onto the next line, so you can continue writing the same string on the following line!

When you wish to print a multiline string that has been broken up using backslashes, Python displays the code as one line. For example:

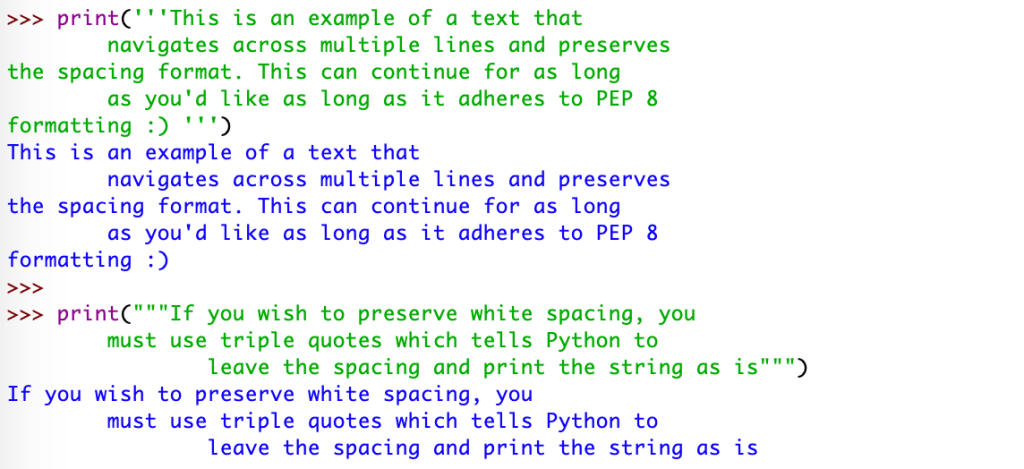

Here is another example of how to write multiline strings. If you wish to preserve the white spaces in your text, you can use triple quotes (”’ or “””) as delimiters:

When you do this, Python preserves the spacing of your text and prints your string on multiple lines with whatever indents you have coded. For example:

Note, the spacing is printed exactly as it was indented in the text.

2.2 Finding the Length of a String

Length is the count of the number of characters that a string contains, including the spaces. The string “jet” has a length of 3, while the string “jet is my dog” has a length of 13. It would be incredibly frustrating to have to count each character and all spaces to determine the length of a string, so Python comes with a built-in len() function which does exactly that!

len() can be used on strings, or strings that have already been assigned to a variable.

Type the following into your interactive window:

To break down what you just wrote: you assigned the string “Jet is my dog” to a variable, “jet”. Then, you used the “len()” function on the variable to find the length of jet, in this case, 13.

Fun Fact: My dogs name is actually Jet! He is a pitbull/lab and german shepherd mix and, in my opinion, the most handsome pupper around! See slideshow below 🙂

Back to regularly scheduled programming…. pun intended. Finding the length can be extremely valuable when you need to explore the text from user input or websites. This isn’t the extent to our string manipulation techniques, there is so much more we can do! Let’s find out!

2.3 Indexing, Slicing, Concatenation

Thus far we have discovered what strings are, how to create strings and string literals, and how to determine some features such as the length. Now, let’s discover some of the crucial things we can do with strings that renders them “fundamental”.

2.3.1 Indexing

An index is the position where each character of a string lies. Each character has a numbered index, or numbered position, within the string. In order to access these characters, we can use the nth position, which is done by placing the number n at the end of the string in between two square brackets.

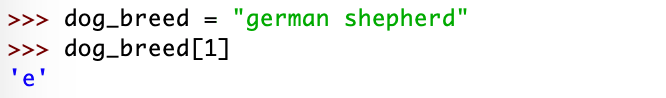

Type the following into the interactive window:

When you call “dog_breed[1]”, you get a returned output of the letter “e”, which is located at position 1 in “german shepherd”.

If you’re wondering why Python didn’t return the first letter in “german shepherd” but instead returned the second letter, you’re onto something!

In Python, as well as most other programming languages, indexing, also known as counting, always starts at zero. It is common for many programmers, beginner and advanced, to forget that counting starts at zero. Often times, an off-by-one error occurs by trying to access the first character with the index of 1 instead of 0.

In Python, as well as most other programming languages, indexing, also known as counting, always starts at zero.

So, how do you return the first letter of the string? To do so, you call the character at position 0. Type the following into your interactive window:

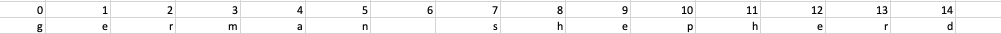

That’s better! Let’s break down the index for each character of the string “german_shepherd”:

As you saw earlier, even spaces count as a character and therefore get their own index number and position.

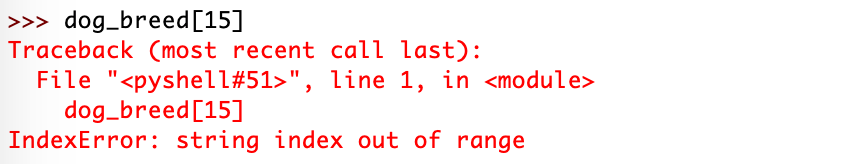

If you attempt to index a string beyond its index length, Python will throw an IndexError, because the largest index of a string is always one less than the string’s length. For “german_shepherd”, since the length is 15, the largest index allowed to be called is 14.

Type this into your interactive window to view the error message:

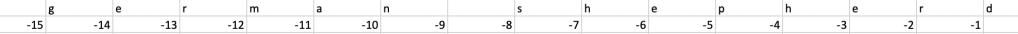

One of the coolest perks when it comes to indexing strings is that you can also use negative indices. This means that you can use the number -1 to index the last character in the string, which is helpful if you don’t know the length of the string or what the last character is. Negative indices work backwards, so -1 is the last character, -2 is the second to last character, and so on. Similar to positive indices, Python will raise an IndexError if you try to call the index that is out of bounds for the given length of characters.

What do you expect to see if you type dog_breed[-3] into the interactive window? Let’s try it out!

Type this into the the interactive window:

Whether you prefer positive or negative indexing, either does the job the same. You may find that negative indexing is more helpful in some instances than in others, but ultimately it is your preference which you use.

2.3.2 Slicing

Knowing how to index a string is super important. But what if you only need the first word of “german_shepherd”? You could index the entire first word by calling the position of all of the letters… it would look something like this…

(W)ooof… that was tedious!

Good thing there’s a much easier way to do this!

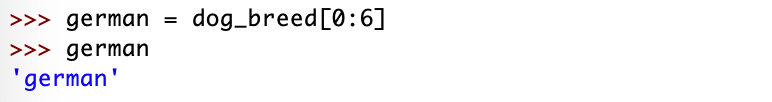

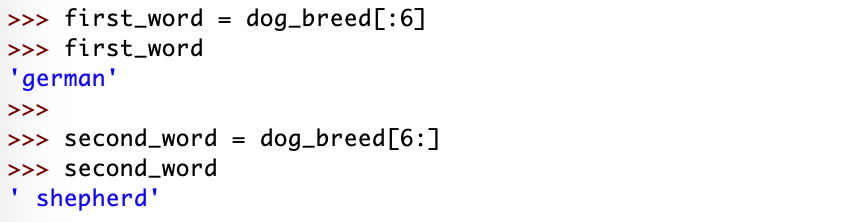

If you need to index more than just the first couple letters in a string, you can extract a piece of the string, a substring, by placing a colon in between two index numbers that are in between two square brackets. To obtain just the word “german” you could do this:

The “[0:6]” part of the “dog_breed[0:6]” is a slice. But wait… why would you use 0:6 when you only want the first five letters? Slicing a piece of the string includes the first number before the colon, and goes up to, but does not include, the last number after the colon.

To recap: similar to equalities and inequality expressions in math, the slice includes the first number before the colon, and includes every number going up to the last number, but excludes the last number.

…the slice includes the first number before the colon, and includes every number going up to the last number, but excludes the last number.

This can be confusing at times, so to make our lives a little bit easier, we can think of stings as an excel sheet with each horizontal row being the sequence of text. To use our “german shepherd” example, this would look like so:

From left to right, you have the numbers zero to the length of the string, in this case, fourteen. Each slot in the sheet is reserved for a character in the string. So for our example of our substring “dog_breed[0:6]”, the output is “german”, since at position zero you have the first character ‘g’, position one the ‘e’, all the way to position six, where we include everything before the character at position six while excluding the character itself.

We can simplify this even further by removing the first index position zero, which allows Python to assume we want to start at the first position. By excluding the last index position (in this case the 6), Python assumes you want to continue the slice from the first included number through the end of the string. Let’s explore this:

Notice that in the second_word, the space is included because we have sliced from, and included, the sixth character, and continued all the way through the end of the string. The “first_word” variable starts at position zero, even though we did not explicitly include the zero, and continues on to include every character up to, but excluding, the character at position six.

In other words, “[0:3]” is equivalent to “[:3]”, and “[6:15]” is equivalent to “[6:]”. If you exclude both numbers and just include the colon, the output will be the entire string:

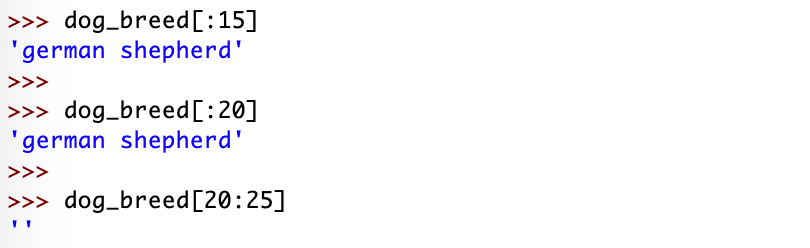

Unlike string indexing, Python will not throw an IndexError if you were to try to slice between two boundaries that are greater than the beginning or ending boundary:

The first example is similar to what you have learned thus far, the string is sliced from the beginning, starting at position zero, through the end up to, but not including, the fifteenth character of the string (since the fifteenth character doesn’t exist). Python will ignore the nonexistent indices and instead returns the full length of the string, which has a length of 15 characters. When you try to slice a string using a range that is out of the boundaries, Python will return an empty string, ”. This is called empty because it does not contain any characters, while a string that contains anything, even just one space, is not empty.

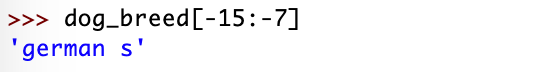

Similar to indexing, you can use negative numbers to slice strings. The rules to slice a string using negative numbers are the exact same as the rules to slice a string with positive numbers. Instead of imagining the excel sheet for the string with positive numbers, imagine that every character is assigned a negative number starting from the end:

The slice “[m:n]” returns an output with the substring staring at “m”, that goes up to, and does not include, “n”.

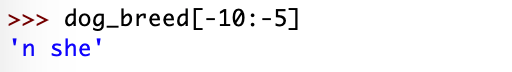

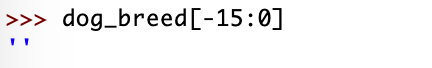

In the first slice, you start at the very beginning of the string (the last negative number) and continue to but not including the -7th character. If you had ended the slice at zero, it wouldn’t work, and would only return an empty string:

The output is an empty string because the zero corresponds to the leftmost boundary, as does -15, and this does not translate to a valid boundary to the right of the first number. To include the last character in your substring, or slice, you can leave out the last number and index the slice with just the first number and the colon.

2.3.3 Concatenation

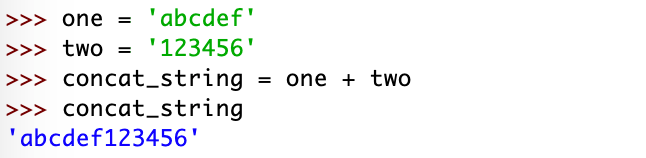

Concatenating a string simply means to combine two strings using the + operator.

Type the following into the interactive window:

To break down what you just did:

- You assigned ‘abcdef’ to the variable “one”

- You then assigned ‘123456’ to the variable “two”

- The third line is where the concatenation occurs. You added the variables one and two together using the + operator to result in the combined, concatenated, variable “concat_string”

- Finally, when printing “concat_string”, you can see that “one” (‘abcedf’) and “two” (‘123456’) are combined

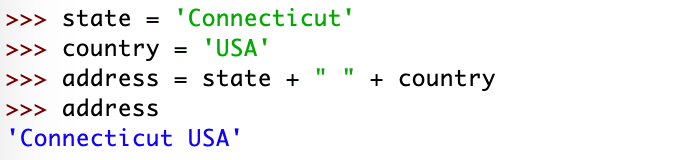

You can also combine two different yet related strings together, for example, if you want to combine a state with its country:

In this example, you concatenated the string assigned to “state” with the string assigned to “country” and included a space in between the two by using the + operator and adding another string, the ” “, before adding the last variable.

The result is a final string consisting of the “state” variable, a space, and the “country” variable.

It is incredibly important to know that strings are immutable. Being immutable means that you cannot change a string after it has been created.

It is incredibly important to know that strings are immutable. Being immutable means that you cannot change a string after it has been created. So, Python will throw an exception if you try to replace a character in a string that you already established:

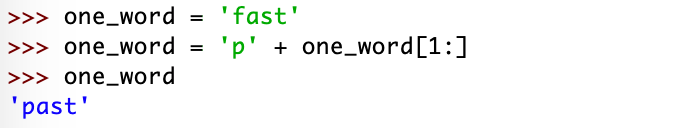

This TypeError means that str objects do not support item assignment; in other words, you cannot change a character of a string once it has been assigned to a variable. The only way to change a string, or alter an existing string, is to create an entirely new string. Let’s change the word “fast” to “past”:

Let’s break down what you just did:

- Assigned the value “fast” to the variable “one_word”

- Concatenated the slice “one_word[1:]” – the string ‘ast’ – with the letter “p”, which turns into the string “past”

- It’s super important to include the colon in order to obtain the end part of the string assigned to the first variable in the new variable

3. Using Methods to Manipulate Strings

Methods are special functions that come built into Python to manipulate strings. While we won’t cover all of the different methods, we will discuss the most common methods used (nearly) every day as a programmer! Let’s begin!

3.1 String Conversion

Sometimes, you’ll want to transform a string that has upper case letters to all lower case, or vice versa. This can be the case if you’re dealing with user input data, and want everything to be all one case. To do so, you can use string methods by tacking on a .lower() or .upper() at the end of the variable or directly at the end of the string.

Note: we will always refer to string methods with a dot (.) in front of the method name in order to differentiate between other built in functions such as “print()” and “len()”

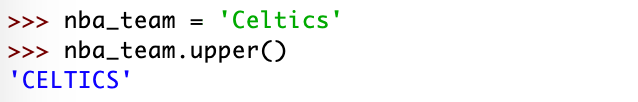

Type the following into the interactive window to apply string methods to strings:

Type the following into the interactive window to apply string methods to variables:

Built in functions such as “len()” and “type()” can be called directly and are independent of other methods. Methods such as “.lower()” and “.upper()” can be used in conjunction with other string methods. We will see more examples of this in the next few sections.

3.1.1 Immutability and Methods

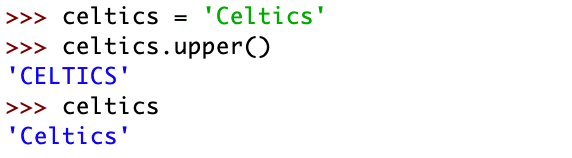

In earlier sections you learned that strings are immutable, in other words, they cannot be changed after you have created them. This may seem confusing because it appears that string methods are altering already creating strings, right? What these string methods do is make a copy of the original string and apply the modifications called. By using these lackadaisically, you could unknowingly create bugs in your code.

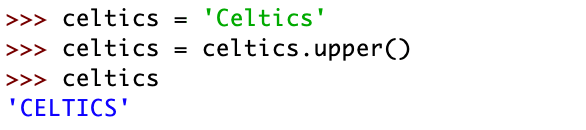

Let’s explore this in the interactive window:

The method “.upper()” doesn’t actually change the variable or string, instead it shows a copy of the string. If you want to change the string and keep the result from the string method, you will need to assign it to a variable:

Let’s explore what you just accomplished. First, you assigned the string “Celtics” to the variable celtics. You then called “celtics.upper()”, which returned the string in all upper case, by reassigning it to the celtics variable. By doing this, you override the original string “Celtics” with all upper case characters.

3.2 How to Determine What Character a String Starts/Ends With

Aside from needing to change the case of characters in a string, you may want to determine what a string begins with or ends with. There are two string methods that accomplish this, “.endswith()” and “.startswith()”.

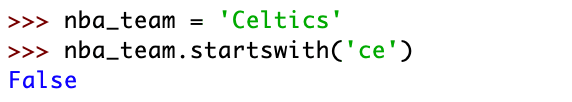

Let’s look at how to use each method. You can use “.startswith()” followed by the characters you wish to check, like so:

To break down what you did: by using “.startswith()” you tell Python to search the string to verify if it starts with the characters “ce”. But wait… Celtics does start with “c” and “e”… so why did Python return “False”? Any thoughts on why this is?

Your string starts with “Ce”… so if you answered that the reason Python returned False is because the “C” in our string is capitalized, then you’d be correct! This is because the “.startswith()” and “.endswith()” methods are case sensitive, so for Python to return “True”, you would need to use “.startswith(‘Ce’)”:

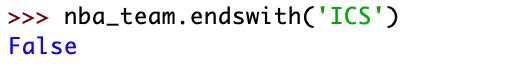

You can also verify the ending of the string by using “.endswith()”. Just the same as “.startswith()”, this method is case sensitive as well:

The values “True” and “False” are not actually string themselves, instead they are Boolean values. We will revisit boolean values at a later time, for now, it is important to know that these outputs are not strings.

3.3 Removing Whitespace

Any character that is printed as blank space is called whitespace. Spaces are whitespace, and line feeds are whitespace. Line feeds are characters that move an output to a brand new line. There will be times where you may want to remove whitespace from the beginning or end of a string. Most situations where you may want to remove whitespace are when the users input data themselves, which could include extra whitespace characters, or an incorrect number of whitespace, by accident.

Let’s look at three important string methods to remove whitespace from strings:

- .strip()

- .lstrip()

- .rstrip()

3.3.1 .strip()

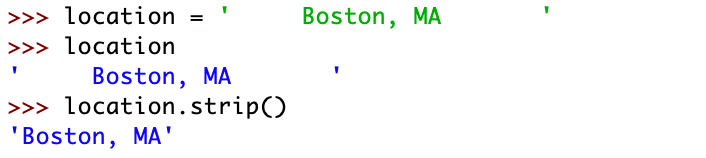

The .strip() method removes whitespace from the left and the right sides of the string at the exact same time:

Here, the whitespace has been removed from the left and right hand sides of the string.

3.3.2 .lstrip()

The .lstrip() method removes whitespace from the left-hand side of the string only:

As you can see, the spaces at the end, or right-hand side, of the string remain intact while the left-hand side spaces have been removed.

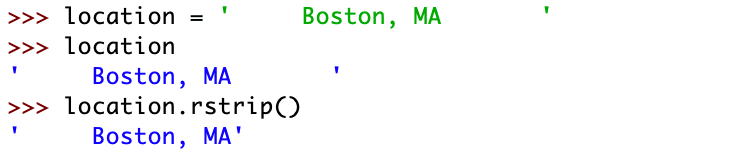

3.3.3 .rstrip()

The .rstrip() method removes whitespace from the right-hand side of the string only:

Here, .rstrip() removes the ending spaces from the right-hand side of the string only, leaving the first spaces intact.

Note: the methods “.strip()”, “.lstrip()”, and “.rstrip()” leave the whitespace in the middle of the string intact, and only remove the whitespace at the beginning or end of the string.

3.4 Showing Methods in IDLE

Another perk of IDLE is that it will display string methods for you to choose and discover new methods. To do this: assign a string to a variable, then type the name of the variable with a dot (.) at the end but do not press “Enter” yet. If you wait for a couple of seconds, IDLE will show you a list of string methods, which you can go through by using the arrow keys.

Type the following into your interactive window:

Now that you’ve assigned the string to a variable “nba_team” you can add a dot (.) to the end of the variable and wait a few seconds before pressing “Enter”. IDLE will show you a list of string methods for you to go through:

IDLE provides a shortcut where you can automatically fill in the name of variables or text without having to type the entire name.

To do this, use the “Tab” key after typing the first few letters of your variable – as long as you don’t have any other variables that start with those letters – and IDLE will fill in the variable name for you.

Step by step:

- Assign a value to the variable “nba_team”

- Type “nba” in the interactive window

- Press “Tab”

- The variable “nba_team” will automatically be filled in

This also works with methods:

- After typing the variable name and the dot (.), type the “u” letter

- Press “Tab”

- Python automatically fills in the line with “nba_team.upper()” because there is only one string method that begins with the letter “u”.

And just like that you are on your way to becoming a master of strings and string methods! Let’s review what you accomplished in this tutorial:

- Learned what a string is, how to create them, and how to use them.

- Learned about different methods to manipulating a string, such as “upper()” and “lower()” to capitalize every character or make every character lower case.

- Learned about string methods to manipulate strings. Learned how to figure out what strings start with or end with by using “.startswith()” and “.endswith()”

- And finally, learned which included stripping strings of excessive whitespace by using “.strip()”, “.lstrip()”, and “.rstrip()”.

Exercises:

- Create a variable named: space_var and save the string ” this phrase has spaces. “ to space_var. Remove the white space from the variable and print space_var.

- Create a new variable, named whatever you like, and save the the string, “this sentence is in all capitals” to is. Convert all the characters in the sentence to upper case.

- Create a new variable named animal, and save the string “dog” to it. Create a new variable that changes the string inside the variable animal from “dog” to “frog”. Hint: use the fact that strings are immutable.

- Create a new variable named “parks” and save the string “yellowstone national park” to it. Slice the string so that only “yellowstone” is returned.

- Create a new variable called “find_length”, and save a string of your choice to it. Find the length of the string you saved. Mess around with the string by adding or removing words and characters and then find the length again.

>>> sweet = “this lesson was super easy to follow”

>>> sweet.upper()

‘THIS LESSON WAS SUPER EASY TO FOLLOW’

LikeLiked by 1 person